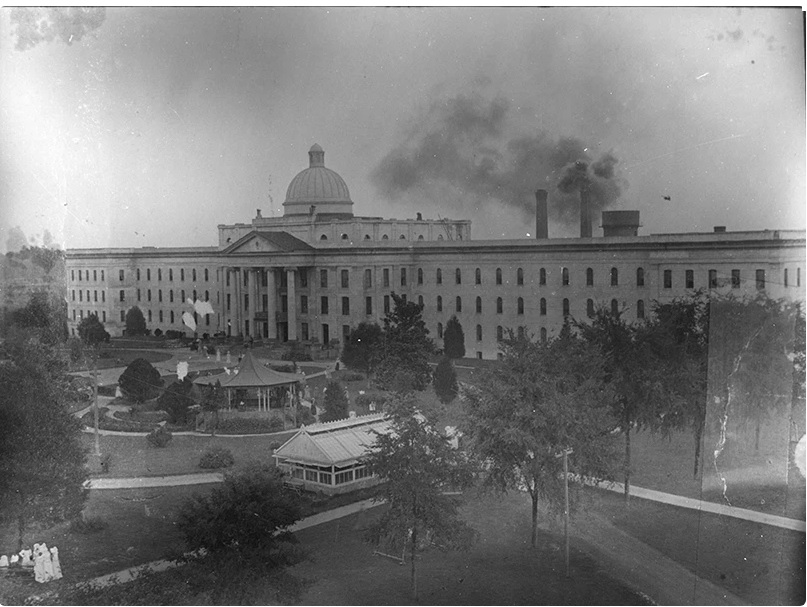

On November 4, 1834, the Georgia General Assembly convened in Milledgeville, and Governor Wilson Lumpkin made a plea on behalf of “the lunatics, idiots, and epileptics.” In 1837, Georgia legislators passed a bill for the creation of a state-operated insane asylum. After five years of construction, the Georgia State Lunatic Asylum opened in 1842. These buildings were constructed near Milledgeville on 40 acres of land that cost $4,000. The first two buildings were planned and constructed by Windsor Lord at a cost of $45,000. These three-story buildings with basements were brick with wood shingle roofs. Over the years, the campus underwent several name changes including Georgia State Sanitarium, Milledgeville State Hospital, and Central State Hospital.

Tillman Barnett, a 30-year-old farmer from Macon, was the first patient admitted to the new asylum in December 1842. He was brought to Milledgeville chained to a horse-drawn wagon by his wife and family, described as violent and destructive. Unfortunately, Barnett died of “maniacal exhaustion” the following summer. Tillman Barnett became the first casualty in a long and dark history of one of the nation’s most notorious institutions.

Dr. David Cooper served as superintendent from 1843 to 1845. Dr. Cooper was instrumental in creating a custodial care institution for Georgia’s mentally insane. During these early years slaves served as attendants to the institution. By 1845, 8 paid employees had cared for 67 patients. There were eight recorded deaths. During this time a committee of the Baldwin County Justices of Inferior Court (equivalent to today’s County Commissioners) governed the facility.

Dr. Thomas Fitzgerald Green commenced his role as superintendent in 1846 and continued in this capacity until 1874. Very concerned with treatment rather than just care, Dr. Green instituted many humanitarian methods to facilitate the improvement of patients so they could return to their homes. By December 1848, the patient population was 90. During that year, there were 20 deaths, 3 escapes, and 14 patients discharged. His success in curing and discharging patients continued during the following years. By the end of his tenure in 1874, the patient population had increased to 696, accompanied by 43 deaths.

During the hospital’s first large expansion under superintendent Green more land was purchased between 1850 and 1854. Green then created a self-sufficient facility with farms, a brick plant, larder, dairy, kitchen, laundry, drying room, smokehouse, barns, stables, workshops, graded land, a cemetery and a circumference wall. The patients did much of the work, not only in the fields, kitchen, laundry and other support systems, but also in constructing some of the buildings. During the Green administration, a Center Building was built to connect the first two buildings, creating a U-shaped facility as the main building on the grounds. Around 1855, a chapel was established in the Center Building, where ministers affiliated with Oglethorpe University, near Milledgeville at the time, along with local ministers, conducted regular services for patients.

Historically, the public’s attitude towards mental illness and those affected by it was characterized by shame. The Annual Reports mention that patients were often quietly left at the asylum, usually near death. Families with financial resources sometimes discreetly transported their mentally ill relatives to another state to escape the stigma associated with these conditions. In keeping with this attitude, Dr. Green refused to give the names of the patients to the census takers in 1860; he only provided their initials. (Note: while this is true for the 1860 Census, the ledger books survive that do include the names of the patients.)

During the Civil War patients hid in the basement and tunnels of the Center Building, which is now the Powell Building. Union General William T. Sherman, who arrived in 1864 on his March to the Sea, spared the buildings because the facility was a humanitarian establishment with no wounded soldiers as patients. However, during the war and post-war years, conditions at the hospital were very poor. After the war, African American patients were added to the hospital population. By 1866 the patient population was 366.

During the late 1860s and early 1870s construction and repairs to the facility began anew. In 1871, the grounds included 1,200 acres, gas lights, heating and ventilating systems, bath facilities and bridges over creeks. By 1873, changes were needed and a more formal plan for regulations, duties and finances was put into practice by a new group of trustees. By 1874, the facility included 2,987 acres with improvements valued at over half a million dollars. Superintendent Green died in 1879 after 38 years of service to Central State as a doctor and administrator.

In the early years of the hospital many patients who died while in the care of the facility were buried in the Milledgeville City Cemetery (Memory Hill). Records of the Baldwin County Ordinary/Judge of Probate indicate that approximately 85 asylum patients were buried in the Milledgeville City Cemetery from 1869 to 1904. The 1845 Annual Report shows a $7.50 burial expenditure. Transporting a patient home would have been very difficult during this time. The body would have had to be transported home by wagon or railroad to limited destinations beginning in the mid-1850’s, and with very little means to preserve the body.

Dr. Theophilus Orgain Powell served as superintendent from 1874 to 1907. As a former Confederate soldier, Dr. Powell managed the asylum with military efficiency. The hospital underwent tremendous growth during his administration and gained international recognition as a first-rate mental asylum. A new Georgia law made the asylum free for all Georgian citizens in 1877. Consequently, the facility was unable to handle the increased patient load. Many of the new patients were people other than the insane or mentally ill. Drunks, the elderly, the chronically ill, the criminally insane, and those with nowhere else to go were sent to the facility for care. In many cases patients extremely sick and near death were brought by family members and left to die. In 1879, the patient population was 754 and the death rate climbed to 197 (Annual Report). The leading causes of death at that time were epilepsy and marasmus. In 1875, a morgue was established in the laboratory.

By 1881, the patient population had grown to 906 patients. Recovery rates and dismissals increased with better treatment. Hospital patients continued to do much of the work to support the facility. Several new buildings were built during the 1880s, as was a railroad spur connecting the facility to Midway, Georgia. By 1898, the railroad connecting the hospital to Milledgeville was completed. To help alleviate overcrowding, a law was passed in 1886 allowing harmless and incurable patients to be sent home. The Milledgeville facility then became a hospital for cure and treatment rather than pauper care for those considered to be social burdens. In 1894 this law was repealed and the patient population once again increased.

In 1895, a large building project added $100,000 worth of new buildings. Dr. Powell also added professional landscaping such as fountains and flower gardens. The population grew to 1,823 with a death rate of 193. Dr. Powell did much to improve the lives of patients. New amusements were added, such as music, billiards, picnics, dances, games, theater, tableaux, and a library. An infirmary with a nursing staff was established in 1897 to help with the rising tuberculosis and pellagra cases. In 1896, more than half of the “Negro deaths” were caused by tuberculosis. In 1897, an operating room was added to the facility. Soon afterwards, the hospital staff began many post-mortem and pathological studies on the diseases and afflictions of the mentally ill.

The hospital’s name was changed to Georgia State Sanitarium in 1898. A dentist was added to the staff in 1900. The year 1903 saw the addition of two new buildings called the Twin Buildings. These four-story facilities were of unusual construction consisting of an octagonal central portion with radiating spoke wings. The “colony farm” that supplied food for the patients and was worked on by the patients was added to an additional 800 acres of land. In 1904 eleven buildings with 72 wards, telephones, and 39 dining rooms were added to the growing facility. At the time of Dr. Powell’s death the population increased to 2,978 with a death rate of 374. Dr. Powell died in 1907 after 28 years of service. The Center Building was renamed to honor the doctor and became known as the Powell Building.

Various hospital departments made items associated with patient burials as part of the hospital’s self-sufficient operation. The 1888 Annual Report lists the construction of 1,142 head and foot boards for the cemetery as “improvements”. During the next few years, until 1902, the carpentry shop continued to make approximately 1,037 headboards and 231 footboards. It is believed that these headboards were marked with the corresponding grave numbers recorded in “Cemetery Records 1880-1951”. In addition to the grave markers, coffin linings, coffins, coffin shipping boxes, and burial pillows were made at the hospital. Burial robes, on the other hand, were purchased from three merchants located in Milledgeville. In 1901, a pair of casket pedestals was likely acquired for use in the chapel during funeral services held at the hospital. A hearse was purchased in 1890 and in 1897, an additional hearse wagon was added to the hospital’s equipment. The hearse was sold in 1901. The 1898 construction of a spur line or “Dummy Railway” into the hospital grounds made it more efficient to ship the deceased home for burial. The first mention of the construction of boxes for shipping coffins was in 1892. The carpenter shop made 117 boxes at that time and there were 194 deaths. In 1907, however, there were 98 shipping boxes for coffins made and 374 deaths. Of these 374 deaths the “Cemetery Records 1880-1951” show that 246 or 66 percent were buried in the cemeteries.

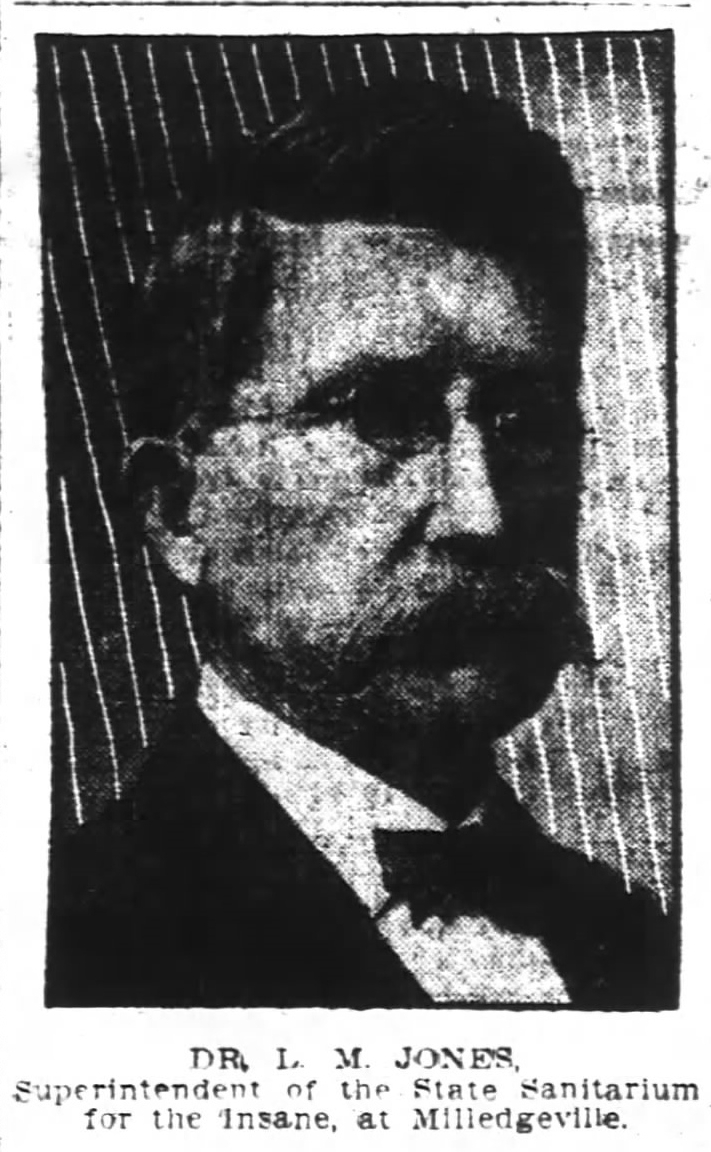

Dr. Loderick Mathews Jones began service as superintendent in 1907 and continued until 1922. During the Jones administration the facility received minimal improvements. Dr. Jones’s primary focus was the farming project. Consequently, the patients and their treatment suffered. In 1915, an assessment of the hospital showed conditions to be very poor. The hospital also gained a reputation for abusive treatment of patients during that period. During WWI (1917-1918) the hospital no longer offered treatment for patients. Instead, reverting to custodial care only. In 1909, the patient population was 3206 with a death rate of 1923. In the 1914 Annual Report a statement dramatizes the growth of the facility: “in twenty years the population of the Sanitarium has increased more than 110 per cent.” The high rate of death during 1914 was attributed in great part to the large number of cases of pellagra and tuberculosis sent to the hospital. The final stages of this affliction caused disorientation and decreased mental capacity. Many of these patients were near death upon arriving at the hospital, and a large number of those patients died within a month of admission. In 1914 the U. S. Public Health Service set up a program at the hospital to begin basic research on pellagra. Patients became research subjects when experiments with diet were conducted until the 1940s. It was then determined that this primarily southern affliction was caused by a vitamin deficiency. For a period of approximately 20 years pellagra was the leading cause of death at the hospital, followed by tuberculosis. In 1918 the death rate was 696 of 4,000 patients and decreased to 474 the next year due in part to the research on pellagra.

Admission procedures changed in 1918 to include the assessment of two doctors and an attorney instead of a jury of six. This was an attempt to limit the population to patients who had a chance of recovery. Another attempt to alleviate overcrowding of the hospital was made in 1919. An Act was passed by the Georgia General Assembly to provide a facility for the care and training of the mentally retarded – those who could not be cured. The school was placed under the State Board of Health and located in the Gracewood Hospital, located near Augusta. This provided a temporary relief to crowded conditions at the Milledgeville hospital. In 1922, the hospital population was 3,972 with a death rate of 283. The leading cause of death was general paralysis of the insane, with tuberculosis being the second leading cause of death. Among the improvements of this administration was the organization in 1910 of a training school for nurses, geared specifically to training psychiatric nurses. Other improvements were electric power, fire equipment, five ward infirmaries, new buildings for children and epileptics, African American housing, a nurses’ hall, seven tuberculosis “pavilions”, hydrotherapy units, and the purchase of embalming equipment. New entertainment such as billiard rooms and new projection machines offered minimally improved conditions for patients. Dr. Jones died in 1922.

The administration of Dr. Roger C. Swint as superintendent lasted from 1922 to 1934. The facility included the Powell Building with six wings, Green Building, Male and Female Convalescent buildings, Twin Buildings, two African American buildings, mortuary, chapel,

laundry, barns, and workshops. The buildings, 3,772 acres of land for the hospital facilities, and the farmland amounted to a total value of $2,781,202. Dr. Swint added a Social Service Department to help patients return to home life. Occupational therapists were added as well as workshops and beauty shops. New entertainment such as live bands, radios, games, and picnics were added to help the patients’

recovery. In 1925 patients were used as research subjects for the treatment of malaria. During this year a statistical study showed a 78% reduction in the death rate from tuberculosis since 1905. During the next two years the death rate from this disease increased but decreased thereafter. The leading causes of death were arteriosclerosis and cerebral hemorrhage. The population reached 6,000 by 1929 with 453 deaths.

In 1929, the admission of the criminally insane and criminals into the hospital became an issue of great concern to Superintendent Swint. In this same year the Georgia General Assembly changed the name of the hospital to the Milledgeville State Hospital. In 1931 the hospital was placed under the Board of Control of Eleemosynary Institutions. In 1933 hospital maintenance appropriations were reduced by 29% due to the Great Depression. Also in 1933, preliminary plans were underway to use the P. W. A. program (a Federal New

Deal program), if passed, to provide improvements in housing and equipment. A political maneuver by Governor Eugene Talmadge in 1934 resulted in the dismissal of Dr. Swint as administrator of the facility.

Dr. John W. Oden served as superintendent from 1935 to 1941. Dr. Oden was the superintendent of the Training School for Mentally Defective Children at the Gracewood Hospital before he became the administrator at Milledgeville. The hospital was transferred to

the newly expanded State Department of Public Welfare in 1937. A Metrazol and insulin shock treatment program came into practice in the 1930s to help certain types of metal disorders. Also, in 1937, the Sterilization Bill was passed, allowing the hospital to sterilize

selected patients as determined by a State Board of Eugenics. In 1940 pellagra was officially identified as a dietary disease. The same year, the Rivers Building, a tuberculosis hospital on the campus of Central State Hospital was established.

During the Dr. L. P. Longino Administration, 1941 to 1943, electrical shock treatment was introduced. It proved to have a calming effect on the patients, thus providing a better working environment, but its health benefits for the patients were not clear. In addition, there were reports of the misuse the electric shock treatment. On a positive note, the occupational therapy program continued to grow and was beneficial for the patients. At the beginning of this administration the patient population was 7,334 and increased to 8,113 in 1943. The death rate was 461 in 1941 with 416 cadavers being embalmed, and in 1943 there were 613 deaths. Dr. Longino resigned for health reasons in 1943.

Dr. Y. H. Yarborough’s tenure as superintendent spanned from 1944 to 1948. Throughout World War II, the hospital experienced a significant shortage of supplies under his leadership. During his administration the hospital underwent a state investigation because of charges that sane people were mistakenly being admitted, and because of very poor conditions. During this time, student nurses were brought in and the Binion Building, a maximum-security building for the criminally insane, was constructed. In addition, a new auditorium was completed in 1946. Although the standards of the American Psychiatric Association were being applied to the operations of the hospital by 1948, they were not yet fulfilled. The hospital population in 1948 was 9,164 with 902 deaths. Dr. Yarborough asked to be relieved from the position of superintendent in 1948.

Dr. S. A. Anderson only served as superintendent of Central State Hospital for 22 days in 1948. The administration of Dr. T. G. Peacock began in that same year. Transorbital lobotomy treatment was administered to some patients, a new tuberculosis unit was created, and a malaria laboratory established in the hospital. The deaths from tuberculosis dropped 87% during the early 1950s, as the nursing staff began to improve.

Between 1949 and 1956 the hospital received 619 personnel additions to the Medical Department. By the 1950s, the hospital was the second largest mental hospital in the world. The hospital hired its first clinical psychologist, Dr. Peter G. Cranford in 1951. In 1952, the Georgia General Assembly passed an act providing for voluntary admission of patients with the certification of a doctor. A religious therapy program was added in the early 1950s, and Jewish services were added to the regular services held in the Arnall Building Chapel or the Auditorium. Patient garden club therapy began in the late 1950s resulting in a large beautification movement. Several new wards were also built during that time.

On May 1, 1952, Dr. Peter Cranford wrote in his book that patients working on a road about 100 yards from the Center Building dug up human skulls and other bones. Superintendent Peacock ordered the work to continue. Another employee, identified as Joe, said this was probably “our oldest paupers’ cemetery.” No other information is available. Legends and rumors indicate that these graves could have been near the pecan orchard north of the Center Building or near the Binion Building. There was no mention of where the remains were reburied.

In 1955, 3,200 acres were purchased for cultivating crops and expanding the dairy. Patients were still doing much of the work, both on the farms and in the buildings. The population rose to 11,748 patients by 1958 with 1,145 deaths. Arteriosclerosis and pneumonia were the leading causes of death. Thousands of people were sent to Milledgeville over decades, often with unspecified conditions, or disabilities that did not warrant a classification of mental illness. The hospital outgrew its resources, and the patient-physician ratio was a miserable 100:1 in the 1950s. Patients were subjected to inhumane treatments including lobotomies, insulin shocks, hydrotherapy, and early electroshock therapy. Children were subject to confinement in metal cages. Adult patients were forced to take steam baths and cold showers. Some were confined with straitjackets and treated with douches.

In 1959, the Atlanta Constitution’s Jack Nelson investigated reports of a “snake pit.” Nelson discovered that the thousands of patients at Central State were served by only 48 doctors, none a psychiatrist. To make matters worse, some of the “doctors” were actually patients who were hired off of the mental wards. The series rocked the entire state of Georgia. In the wake of the scandal, asylum staff were fired, and Nelson won a Pulitzer. The state, which had ignored decades of pleas from hospital superintendents, began to provide additional funding. As new psychiatric drugs allowed patients to move to less restrictive settings, Central State’s population began to steadily decline. A decade before the national movement toward deinstitutionalization, Georgia governors Carl Sanders and Jimmy Carter began emptying Central State in earnest, sending mental patients to regional hospitals and community clinics, and people with developmental disabilities to small group homes. However, this approach has been riddled with tragedies, such as homelessness and drug abuse.

The I. H. MacKinnon administration spanned the years 1960 through 1966. During the mid-1960’s the state government established a regional hospital plan to distribute the more than 12,000 patients packed into the Milledgeville facility. Hospitals at Atlanta, Rome and

Thomasville were either built or adapted to take some of the patients from the over stressed Milledgeville facility. Between 1959 and 1964 increased funding allow the hospital staff to be doubled and the number of doctors on staff tripled. From 1962 to 1964 five chapels were constructed using donated funds. Chapel number two was built on Lawrence Road across from the Asylum Cemetery in 1964. Prisoners were moved into several buildings previously used as hospital wards. The hospital opened “the world’s largest kitchen under one roof” to serve all patients, staff and prisoners in the prisons on the hospital campus. A clinical pastoral training program was instituted in 1963 to instruct clergy on how to administer to patients and prisoners. The Garden Clubs of Georgia, Inc. sponsored the hospital Garden Clubs, offering assistance and funds. The hospital population was 12,205 in 1965 with 1,046 deaths.

In early 1960, the three cemeteries were closed and a new fourth cemetery was created further south on the hospital grounds. The number of patients buried in the hospital cemeteries was steadily decreasing. The attitudes of the public were changing toward the mentally ill and more families were taking their family members home for burial. By 1964 approximately 92% of deceased patients were sent home for burial. In 1965, 1,046 patients died, and the hospital chaplains conducted 60 funerals.

In the 1962 Annual Report there is mention of the donation of a fence for the cemetery from Mrs. Gene C. Goslee of Atlanta. This donation was probably for the Asylum Cemetery but there is no indication where the fence was placed, or which cemetery benefited

from the donation. The hospital Maintenance Section of the Horticultural Division was responsible for grass cutting. To make the job more efficient it appears the maintenance crew removed many of the grave markers to mow grass in the cemeteries. Some markers may

have been replaced for a period of time but over the years the grave markers were misplaced or piled up along the edges of the grounds of the cemeteries. A 1964 photograph of the Asylum Cemetery shows some grave markers in place, but many were already gone.

During the administration of James B. Craig the name of the facility was changed to the Central State Hospital by the Georgia General Assembly in 1967. By 1967 the hospital population was beginning to decline. Better treatment programs, the placement of patients in

qualified nursing homes, and the transfer of patients to other State regional hospitals all helped to reduce the patient load. The farming and dairy operation at the hospital “Colony Farm” was terminated in 1967 by order of the State Board of Health. In 1968, the Garden Club of Georgia, Inc. created a rehabilitation garden on Vinson Highway south of the Rivers Buildings. In 1969 plans were underway to build a new medical hospital on the grounds at a cost of 6.8 million dollars. The Central State Hospital complex/campus contained 135

buildings. The employee work force was 4,072. The hospital still functioned like a self-sufficient city. By 1972 the population was 7,118 with a death rate of 709.

An Executive Reorganization Act created by Governor Jimmy Carter in 1972 placed all the facilities under the newly created Department of Human Resources. In 1975 the regional hospital system included mental health facilities at Atlanta, Augusta, Columbus, Milledgeville, Rome, Savannah, and Thomasville. Between 1966 and 1978 the Asylum Cemetery was still receiving minimal maintenance for some of these years, but the grave markers were becoming lost, displaced by maintenance crews, or covered with dirt. At some time, date unknown, fill dirt was put over several graves and the markers were completely covered. Other grave markers were pushed into the ground or covered by dirt from erosion. South Camp Creek Cemetery and New Colored Cemetery were left to the forces of nature and became overgrown.

The John Gates administration began in 1978 and continued until 1983. In 1982 the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care Organizations accredited the Central State Hospital. Myers R. Kurtz became its superintendent in 1983. In 1988 the Mercer University

School of Medicine began the hospital’s first medical research in more than 20 years. In 1992 Central State Hospital operated the second largest combination hospital and prison facility in the nation. The facility provides residential care for developmentally disabled persons from a 51-county area. In addition, the Forensic Services Unit operates as a maximum-security facility for clients who cannot be placed in other hospitals.

By the 1990s many of the hospital buildings have been taken over by the Department of Corrections. A 1999 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in a Georgia case allowed patients with mental health problems to choose community care over institutionalization if a professional agrees. By the 1990s, the Asylum Cemetery was overgrown. The identity of the New Colored Cemetery had been lost and was believed to be a tuberculosis cemetery because of its proximity to the Rivers Tuberculosis Hospital. This cemetery was also overgrown. The location and the identity South Camp Creek Cemetery had been completely forgotten and obscured by vegetation.

In 1997 the Georgia Consumer Council, a consumer advocacy organization, visited the Asylum Cemetery. The members of this group were former patients of the mental health systems in Georgia. When the members saw the facility, they were appalled by the condition of the cemetery. The Georgia Consumer Council joined forces with the State to clean the site and restore to their original location as many metal grave markers as possible. Replacing the markers turned out to be an impossible task. The group then decided to erect a gate, fence and a statue to memorialize the people buried in these long-forgotten graves. The iron gate and masonry fence were constructed as an entrance to the Asylum Cemetery in 1997-98 and are replicas of ones built on the hospital campus approximately a

century ago. An historic photograph was used as the guide for the reproductions. Soon afterwards, a hospital employee, Byron “Bud” Merritt, discovered South Camp Creek Cemetery while he and his wife were hiking in the woods on the hospital property.

On October 7, 2001, a bronze angel statue was erected in the Asylum Cemetery. The statue was purchased with $35,000 raised by the Georgia Consumer Council. In early 2003 an historic marker was placed near the entrance gate and the cemetery was finally given

a name, Cedar Lane Cemetery. At about that same time, a memorial comprised of 2,000 displaced markers was established a little west of the entrance. Soon after the Georgia Consumer Council rediscovered the cemeteries of the Central State Hospital, other state hospitals across the country started identifying their lost or forgotten cemeteries. In 2001 the members of the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD) issued a position statement supporting the restoration of psychiatric hospital cemeteries, the main purpose being to convey dignity, hope and recovery for consumers of the mental health system and to change the image of mental illness. By October 2001 at least 12 states had begun efforts to restore their forgotten psychiatric hospital patient cemeteries.

The average client population at Central State Hospital was 1,100 in 2002. Following a 2010 agreement with the federal government, Georgia moved all mentally and developmentally disabled patients to community facilities. The same year, Central State stopped accepting new patients. After legal battles and federal investigations revolving around patients’ rights, Central State Hospital and the entire Georgia mental health hospital system were downsized in 2011. Once encompassing more than 200 buildings, the actual state hospital occupies only a half-dozen buildings on roughly 65 acres and currently serves about 150 criminal justice system defendants deemed mentally unfit to stand trial.

The Central State Hospital Local Redevelopment Authority (CSHLRA) was created in 2012 by the state to revitalize and repurpose the property. Led by Milledgeville native Mike Couch, the authority has worked with real estate experts to develop a plan for reusing the property for businesses, schools, and recreation. By the end of 2015, the Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities (DBHDD), which operates at Central State, occupied only 9 buildings. The CSHLRA has brokered several building sales for commercial uses and done such other work as erecting historical markers, but it has not taken control of all of the buildings.

In 2021, CSHLRA unsuccessfully sought federal funding to acquire and either demolish or preserve several buildings, as reported in the Milledgeville Union-Recorder. That plan would save the Powell, save the facade of the Walker while razing the rest, and razing the Green and Jones buildings, an apartment building, and the steam plant. In October 2022, it was announced that asbestos abatement would begin on the Jones, Walker, and Green buildings, and each one was fenced off. DBHDD claimed at the time that the abatement was an urgent response to trespasser-related safety issues and separate from any potential demolition or other long-term plans.

In July 2023, Governor Brian Kemp signed an executive order, clearing the way for the demolition and razing of four buildings on the Central State Hospital campus. These buildings are the Jones, Green, and Walker buildings and a fourth building known as the Wash House building which is located behind the Powell building. DBHDD spokesperson Ryan King, explaining that the “timeline is to be determined.” King said that demolition was found to be “the only viable option” for the buildings and that a revitalization plan is still on the table that will have the Powell Building as a “centerpiece.” Kemp’s executive order states that the DBHDD had requested authority to demolish the structures via a June 29 resolution. A slideshow of items presented at the board’s June meeting says that demolition of the buildings “improves property marketability.” In the case of the Green, Jones, and Walker Buildings, trespassing issues were also given as reasons for seeking demolition authority.

The Georgia Trust for Historic Preservation and the Atlanta Preservation Center (APC) are voicing opposition. Georgia Trust President and CEO Mark C. McDonald noted that his group put the hospital campus on its “Places in Peril” list of endangered historic sites in 2010. “Since that time, we have been constant advocates for the preservation of these culturally and architecturally significant buildings, even going so far as to make grants to projects on the campus,” he said. “We would like to ask for a reprieve of this order to allow all parties to meet to pursue any avenues to avoid the demolition of these structures.” APC Executive Director David Yoakley Mitchell, in a July 27 letter to state officials, noted the complex history of the 180-year-old, 1,400-acre hospital campus, which was a pioneer in mental health in its day before becoming notorious for abuses and a focus of reforms. “The complexity and challenge of this discussion is fraught with emotion,” he said. “Yet the ultimate loss will be the experience of the patients that lived and died there, the families and residents affected by this place, and most of all, what it exposed of who and what we are. The removal of these buildings will be an erasure of all of that and more.”

Thank you for reading. Please share the blog with your friends. I appreciate the support. You can find me on Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok. For more photos of Central State Hospital and other locations from across Georgia, check out my books Abandoned Georgia: Exploring the Peach State and Abandoned Georgia: Traveling the Backroads.

Discover more from Abandoned Southeast

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

It’s sad to see these old antebellum mansions abandoned and falling apart. I’m glad to hear the Rockwell is being renovated. So much history, if these walls could talk…

Great photos.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Really cool piece! (Saw your post in the community pool) There was an abandoned asylum not too far from where I grew up that I and others visited many times in our teen years. There is definitely a unique appeal and draw to those kinds of places.

-John

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating text and beautiful pictures. Very atmospheric. Looking forward to working my way through your earlier posts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nice piece…I need to ask my sister-in-law if she know about this place. She grew up in Milledgeville and she and my brother married in the historic district.

LikeLike

The Rockwell Mansion has been partially restored, and is on the market for $350, 000. I grew up in Milledgeville, now live in Atlanta, so that price seems like a steal.

LikeLike

It’s a steal, but you have to have VERY deep pockets to restore them as they should be done. No mass produced overseas crap can be used and real craftsmen should be doing it.

LikeLike

Thanks for this post. I’ve been to Milledgeville many times through the years and have always heard stories of the mental hospital but have never seen it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve actually seen all these buildings myself while i was at a military school in Baland circle which is the entrance to the lunatic asylum . We were told that all the abanded prisons and hospitals, and mansions were haunted

LikeLiked by 1 person

Maybe. There’s no telling.

LikeLike

I was in Rivers state prison 2006 and some of 2007 and yes there was something there other than us inmates.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tell us about what you experienced.

LikeLike

What did you guys experience

LikeLike

My grandmother died there. During her child bearing years she started loosing her hearing and became completely deaf. No one could communicate with her and she was always lost. Her family put her there because nobody took time to try to help her learn to communicate. Mother said she wasn’t crazy, only deaf . So sad, very sad.

LikeLike

After I initially left a comment I seem to have clicked the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and now each time a comment is added I receive four emails with the exact same

comment. Perhaps there is a way you can remove me from that service?

Cheers!

LikeLike

I can’t remove you but you may be able to unsubscribe in the emails. Sorry about the confusion.

LikeLike

I graduated from Georgia College in 1990. Part of my teaching degree was to log so many hours at Central State. I could not tell the staff from the insane. I even played checkers with a man that had killed his brother. I will never forget going there…

LikeLike

The reason I have family in Milledgeville is a few decades ago, on my mom’s side we had somebody who got shorted on their paycheck and took an axe to the boss’ house, broke down the door and killed him with said axe. He was sent to Milledgeville Asylum. Even after being deemed fit to leave, he chose to stay as a janitor there, as he was afraid he’d kill again. It’s neat to actually see it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, what a story. Thank you for sharing.

LikeLike

My Aunt worked in one of the buildings that has been repurposed at Central State. Specifically, she worked in the giant kitchen that is right across from the original morgue. Her back dock looks over most of the grounds there. Also, back in the 80s, my uncle worked in the hospital itself. They had all sorts of people who were confined there, but one of the worst, at least for him, was a patient that was bed-bound obese. She also was HIV positive, and would attempt to bite anyone who attempted to move her. It would take at least 8 guys to get her moved from one point of the hospital to another for various doctors. It was not a great job.

Finally, my aunt and uncle obviously live in Milledgeville. They have four daughters, and my uncle would get scared out of his mind when they were teenagers every morning. Their hair dryers had the same tone as the alarm for an escaped prisoner from the hospital.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love reading these stories. Thank you for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for stopping by!

LikeLike

I loved the story thank you so much for sharing it was very cool, now i want to go check it out someday.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading. It is definitely worth a stop!

LikeLike

I was once an inmate at Rivers in the 80s. The place was so primitive. Basically, not fit for human beings, but that’s what is expected from a state like Ga. They still have slavery, it’s simply instituted via the prison system. They should have torn that building down decades ago. Most of the crime committed there was by the administration. I discovered the warden at the time was using inmate labor for pay he received. I was there for years, and got a check for $25 minus tax. The eating area only held about 15 people at a time, it rained inside, only 3 people could use the toilet at a time, and you sat, side by side. The place was full of bugs, due to window problems. If it was meant to be a place for lunatics, by the time you left, you’d fit the bill. Tare that mother—— down.

LikeLike

In the 1940’s. there as a young girl who lived near us who was committed to this hospital . She never returned home. When they closed the hospital she was declared unfit for any type of rehab. Maybe she remained until she died. Gerri

LikeLike

One of my aunts spent ten years in this place, 1961-71, from age 30 to 40. I never knew the full details of how she ended up there, but serious depression runs on that side of my family. She received SSI after her release and spent the rest of her life in the home of her oldest sister & BIL in Palmetto, and my memories of her are of a quiet but definitely not “insane” woman who smoked unfiltered cigarettes and loved cats. She passed away in 1996, and rarely ever spoke of her time at the hospital.

LikeLike

That’s so sad…. I’m really glad she didn’t have to spend her entire life there though. I do hope her sister and brother-in-law took good care of her! ❤️

LikeLiked by 1 person

They lived in a rural place where she could have her cats and take long walks and fish, and they grew all their own food, which was good since I don’t think she would have fared well in the city. She did have a safe haven after being released from that place. So many others who spent time there had it much worse.

LikeLike

^^This is me(Sonja)replying.

LikeLike