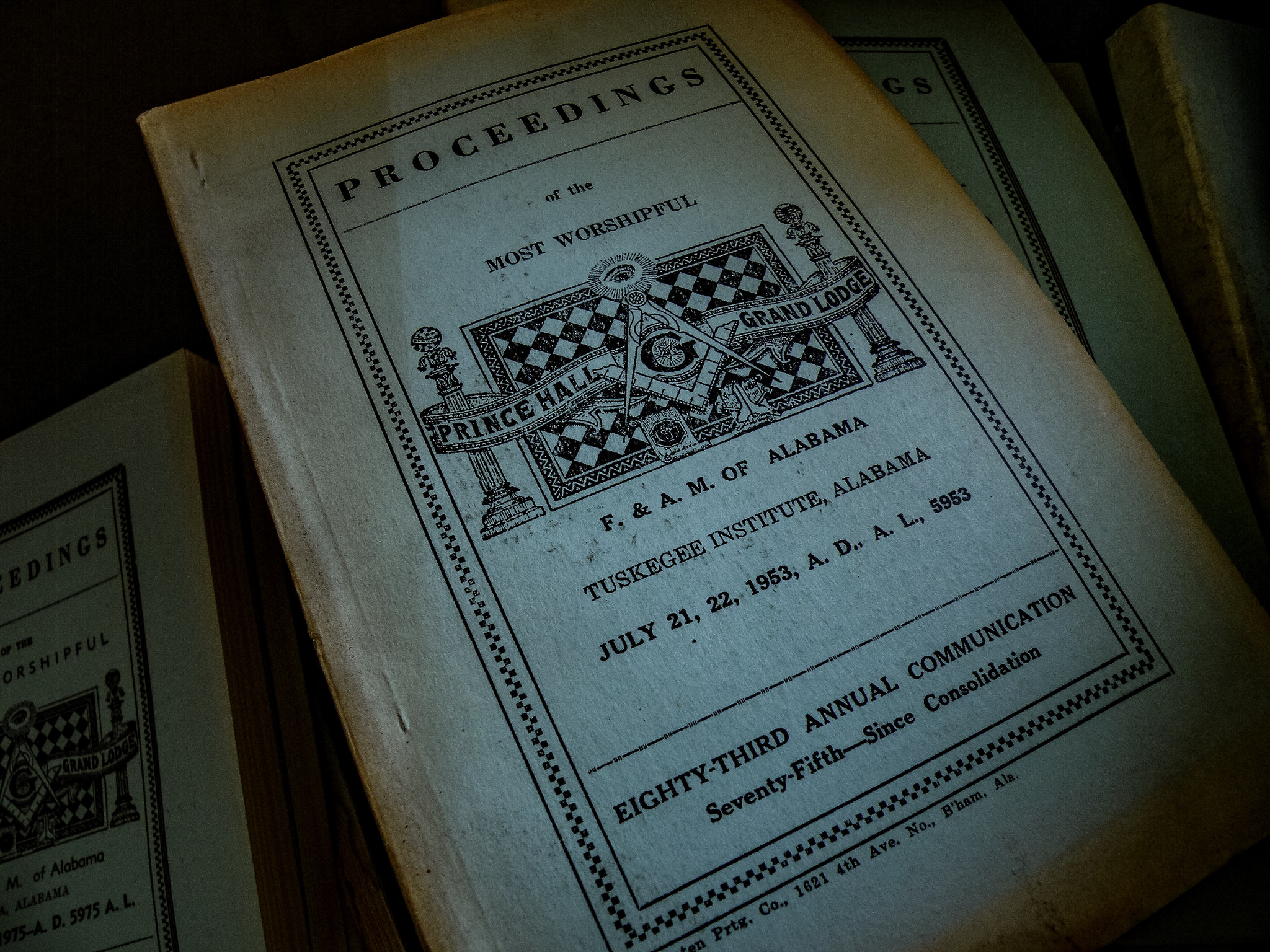

There were roughly ten African-American lodges already in existence by 1870, when the “Colored Grand Lodge in Alabama” was organized in Mobile under the guidance of the Grand Lodge of Ohio (due to the absence of local white sponsorship). Soon after Freemasonry in Alabama thrived, with lodges springing up in Mobile, Montgomery, Selma, Huntsville, and upstart industrial Birmingham, but also in rural communities scattered throughout the state. All of the lodges would eventually come under the umbrella national organization named for Prince Hall, the First Worshipful Master of America’s first Black lodge, established in Boston in 1784.

After 1900, Birmingham surged forward to become Alabama’s largest city, and the Masons were determined to build a state headquarters downtown. They wanted a notable flagship building that would also be commercial space for Black businesses and professionals, in a state where most such venues were unavailable to Blacks. In the early 20th century, there was no such thing as a Black business district in the South. Jim Crow laws authorizing the separation of races excluded African-Americans from white-owned businesses across Birmingham and forced many Black businesses to move downtown in and around the Fourth Avenue Business District. Over the years, the area became a booming hub, complete with packed theaters and vibrant city life that included restaurants and jazz clubs.

Grand Master Walter T. Woods, who was also an architect, spearheaded the project, and planning for the new building began in 1913. However, construction would be on hold for several years as more funds were slowly raised from Masons throughout Alabama. Two members of the Tuskegee Institute architectural faculty, Robert Robinson Taylor and Louis H. Persley were engaged to develop drawings and specifications for the Temple. Taylor, a native of North Carolina and the son of a carpenter, was the first Black student to attend MIT. Under his eye, in collaboration with Institute founder Booker T. Washington, the Tuskegee campus had taken shape over the previous two decades. The much younger Persley was from Georgia, a 1914 graduate of Carnegie Tech in Pittsburgh who had returned South to join Washington and Taylor at Tuskegee.

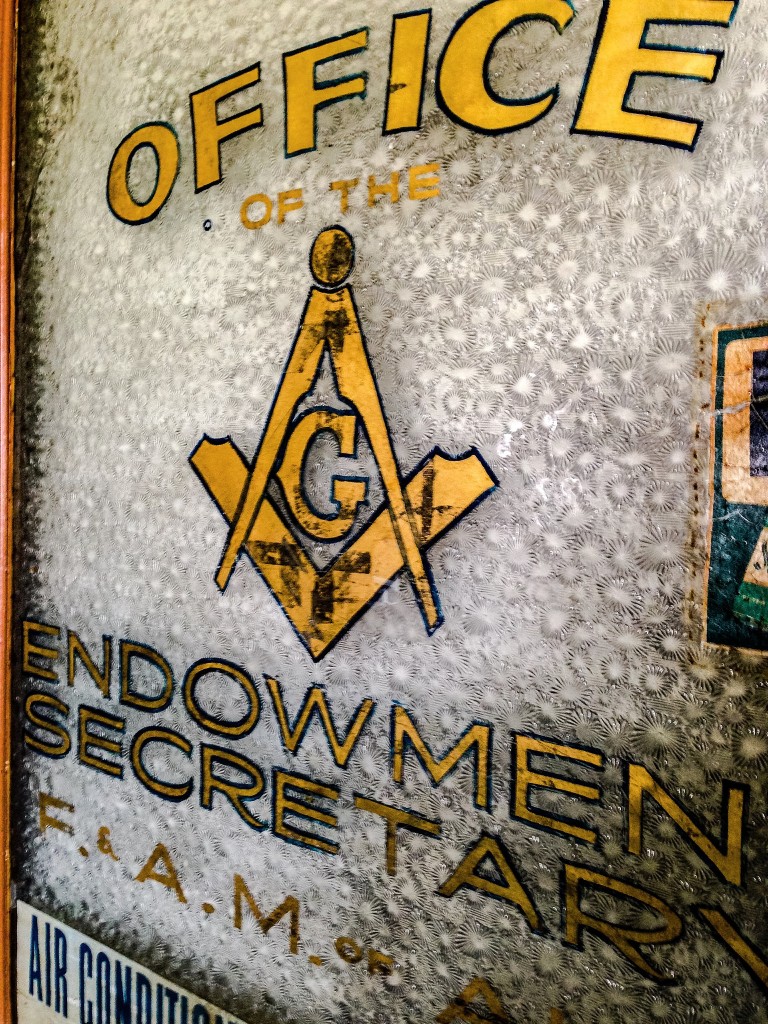

The cornerstone for the Birmingham Masonic Temple, officially named the “Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Alabama,” was laid with an appropriate ritual in 1922. The seven-story Renaissance-revival structure has a steel skeleton, the form of the building was conceived by its designers as essentially a large, quadrilinear commercial edifice. Its larger purpose is symbolically suggested by the thin neoclassical applique that wraps around its two street fronts. Yet the effect is achieved somewhat awkwardly, as pilasters, pedestals, and intervening entablatures stretch to accommodate the functional demands of a many-windowed, multi-storied structure that was to be at once institutional, ceremonial, and commercial. The limestone-faced ground floor of the building is treated as a classical podium that projects slightly at the main entrance to carry four engaged Corinthian columns. Rising through four of the seven stories to an abbreviated pediment flattened against the buff-colored brick facade of the building, the columns announce the main entrance. Inscribed in the tympanum of the pediment is the name by which the building was known in the beginning, the “Colored Masonic Temple.”

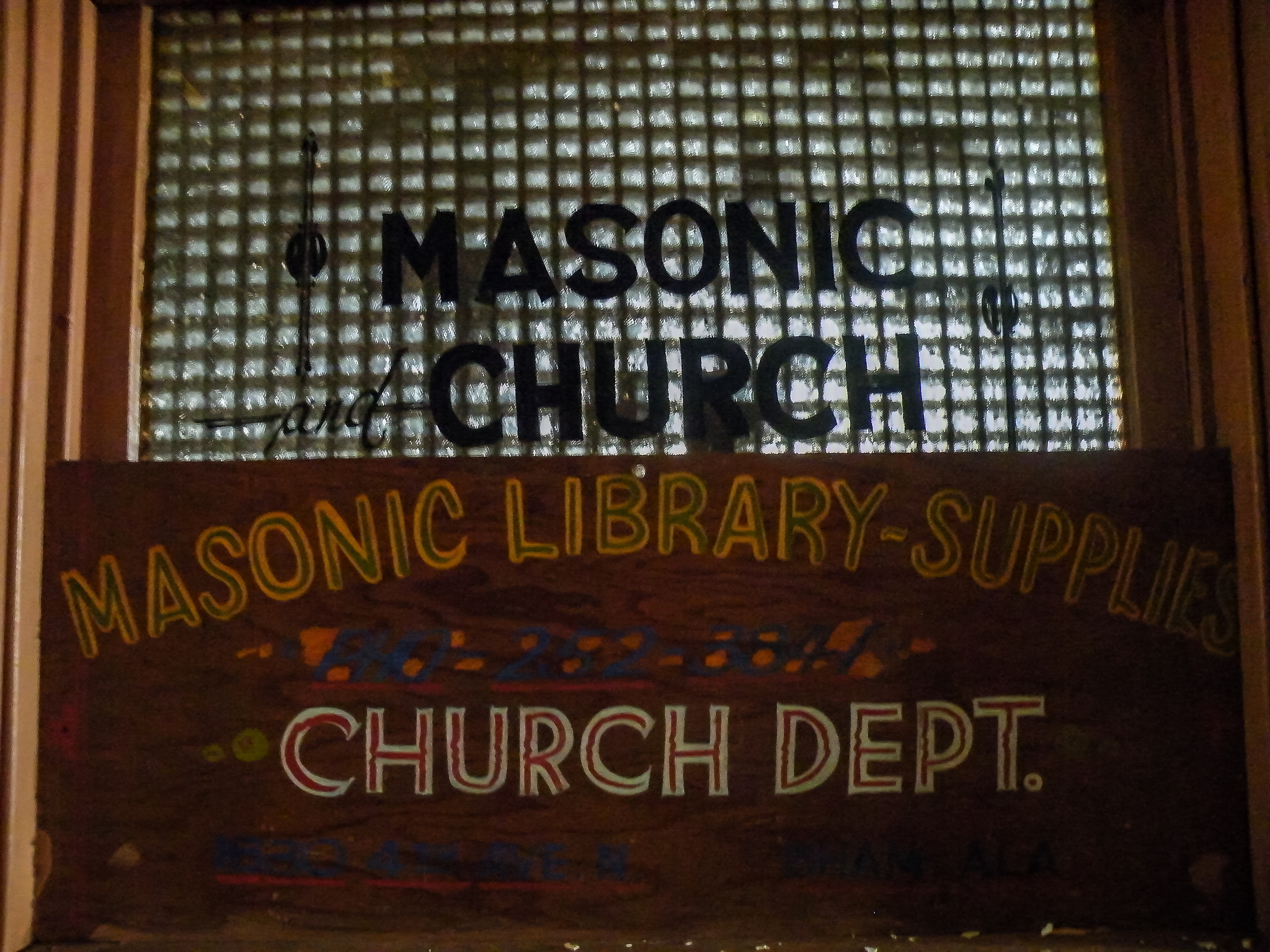

Besides housing the state headquarters for Prince Hall Masons, the building was a hub for the Black community and accommodated the offices of other Black fraternal groups including Freemasonry’s counterpart for women, the Order of the Eastern Star. Black physicians, lawyers, dentists, and insurance agents leased space throughout the building. Three of the ground-floor rooms were occupied by the Booker T. Washing Library, the first lending library open to Black citizens of Birmingham. Adjacent was a popular drugstore and soda fountain, and in the basement was a billiard hall. Besides being the setting for Masonic rites, the 2,000-seat grand auditorium occupying the second and third floors hosted concerts – Duke Ellington, Erskine Hawkins, and Count Basie were regulars – as well as dances, mass meetings, and other special events.

In October 1932, the Communist Party-affiliated International Labor Defense held a civil rights conference in the Masonic Temple auditorium. It was a response to the infamous Scottsboro Boys trial, in which nine innocent Black teens were accused of rape. The gathering was one of the first major civil rights events in Birmingham, setting the stage for future civil rights actions in the city. In time, the building would figure in the civil rights struggle as it sheltered the offices of the NAACP, the Southern Negro Youth Congress, the Right to Vote Club, and the Jefferson County Negro Democratic Youth League. Civil rights lawyer Arthur Shores also had his offices in the Temple Building. The state headquarters of the NAACP was padlocked in 1956 when a state judge banned the organization from operating in Alabama.

The State of Alabama Department of Archives credits this Colored Masonic Temple with creating the second major wave of African-American businesses in the city of Birmingham. In recent decades, with the decline of Freemasonry, a building that once figured prominently in a vibrant black urban life has faced a sort of functional obsolescence. After serving the Birmingham community for more than eighty years, the Prince Hall Masonic Temple was shuttered in 2011. Current plans envision an eventual repurposing of the structure as part of the general revitalization of downtown Birmingham. The Prince Hall Masonic Temple is listed on the National Register as a part of the 4th Avenue Historic District. The Prince Hall Grand Lodge still owns the building, but the grand auditorium hasn’t been used for meetings since the early 2000s. The Masons moved out of the building in 2011 to an adjacent building to save on maintenance costs. Sadly, the Temple has fallen into a state of disrepair. Several windows remain boarded up, but the future seems bright for the blighted structure. Efforts to restore the Masonic Temple to its former grandeur are currently underway.

Thanks for reading. I appreciate the support. Please share the blog with your friends.

You can find me on Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok. For more amazing, abandoned places from across Alabama, check out my books Abandoned Birmingham and Abandoned Alabama: Exploring the Heart of Dixie.

Discover more from Abandoned Southeast

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Great article!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for that wonderful article.

LikeLike

You are most welcome!

LikeLiked by 1 person

So much history wrapped up into on place.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Did you take these pictures? Nicely done!!!!!!

LikeLike

Of course!

LikeLike

This is really good. I liked it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very powerful article. We are gonna share on our site. Thanks much for sharing this article with the world.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for reposting!

LikeLike

Fascinating. Loved this

LikeLiked by 1 person

Revive Reclaim Rejuvenate Its history and should be preserved

LikeLike

As a Mason great learning moment here, thanks

LikeLiked by 2 people

As a Black child and teen, I visited the Masonic Hall frequently. Our family doctor, Dr. Bradford was there. Dr. Bradford also made house calls. As a teen i attended dances there in the Grand Hall. One of my mother’s best friends was a secretary with Booker T. Washington insurance . There was a set of apartments for Blacks in Ensley called Prince Hall apartments. I have wonderful memories from that era.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Wow, so much history in one place. Thanks for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As a Mason I would hope that somehow this building could be saved.

LikeLike

Did you take the books with you?

LikeLike

I did not. They are probably still there.

LikeLike

I have certainly enjoyed my study of the 8 Yellowstone Dr. Old Bridge Twp. masonic building yet it breaks my heart to see the ruins that the building is in today.

It seems that the struggles that the black men and women of yesteryear was/is in vain because of the lack of interest

to maintain the history or these sacrifices and accomplishments. I am a former OES and past the productive age now but I wish that I could in some way instill a little enthusiasm in the youth of today .the Greek words “enthusiasm”

To be faithful over a few, is to be ruler over many

LikeLike

My father , prior to his death, was a 32nd degree Mason. I have mostly no idea what that means. Please enlighten me if

LikeLike